Minimum DataBase

A chronic prostatitis case study: Custard

Courtesy of Susana Silva, Internal Medicine Consultant

Background information

Name: Custard

Age: 8 years

Breed: Golden Retriver

Gender: Male entire

Presenting reason

Inappetence

History

Two-week history of reduced appetite.

Physical examination

Unremarkable apart from the presence of a soft, mobile 1.5cm mass over the lateral thorax that had been present for 2 years with no recent change in size. On rectal examination, the prostate was symmetrical and non-painful; size was considered appropriate for an entire male.

Diagnostic plan

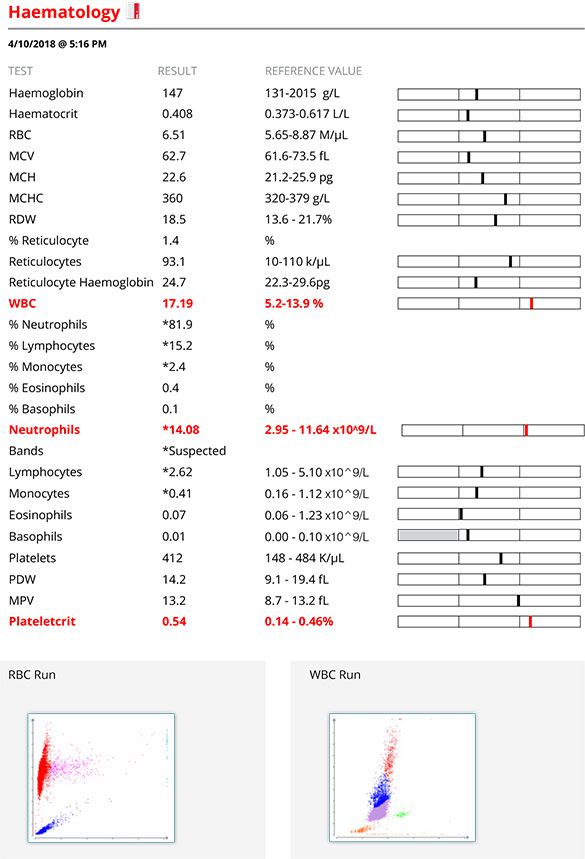

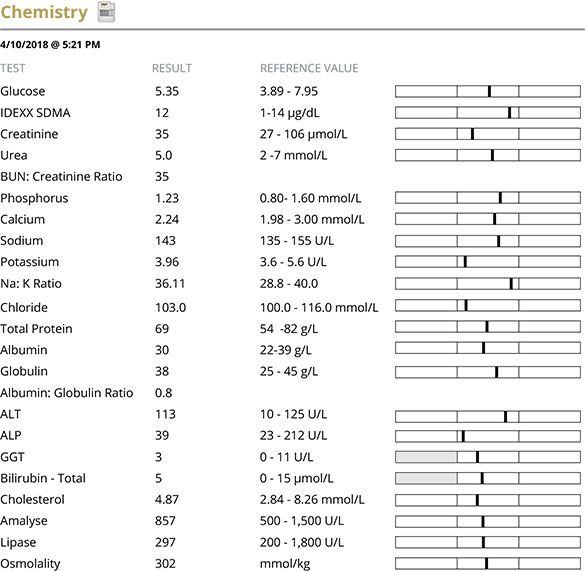

A minimum database (MDB) comprising haematology,biochemistry, electrolytes and urinalysis was performed to assess the main body systems for any cause of the dog’s inappetence..

Interpretation of results of diagnostic tests

Haematology was unremarkable except for mild neutrophilia. A smear was examined which confirmed the white cell count differential and identified the neutrophils as mature neutrophils. Potential differential diagnoses for the neutrophilia would include stress leukogram, infectious, inflammatory, immune-mediated or neoplastic disease. Biochemistry was essentially normal excluding significant renal or hepatic disease.

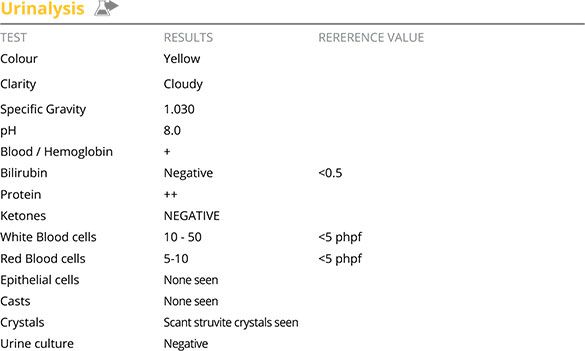

Urinalysis showed the presence of increased white blood cells consistent with an inflammatory sediment despite the absence of urinary tract signs. The ++ protein could be secondary to the inflammatory sediment and should be monitored and, if persistent despite resolution of the inflammation, a urine protein creatinine ratio should be performed.

Further diagnostic assessment

Abdominal ultrasound was performed, with emphasis on the whole of the urinary tract and the prostate. The only abnormal finding was changes in the prostate consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

The prostatic changes were within expected limits for an older entire male dog. However, as no source of the inflammatory sediment had been identified and routine urine culture was negative chronic prostatitis was considered and further investigation recommended.

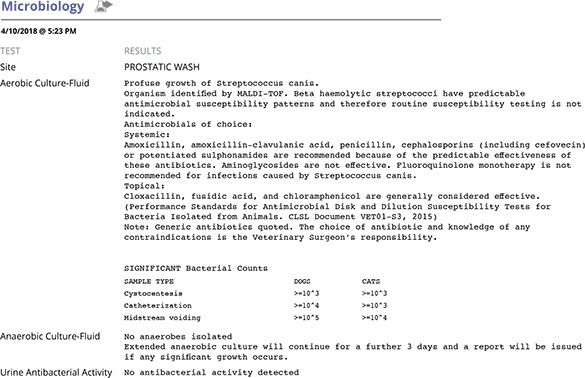

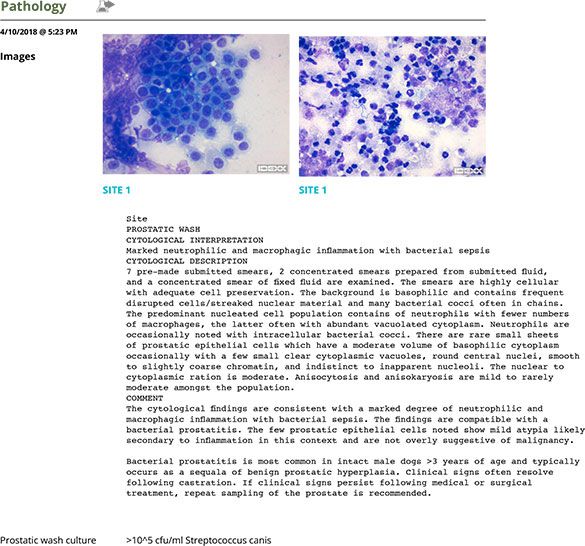

A few days later the patient was readmitted for general anaesthesia and a prostatic wash was performed which was submitted for cytology and culture.

Diagnosis & Treatment plan

The results confirmed prostatitis (likely chronic given the minimal clinical signs). The blood prostate barrier provides treatment challenges as it can limit the penetration of antibiotics into the prostatic tissue, especially in chronic prostatitis. As a general rule, antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones or trimethoprim sulphonamides (TMS) are considered appropriate choices for prostatitis (PROTECT ME poster, SAMSoc/BSAVA1 ). The optimum treatment length is controversial but typically 4-6 weeks treatment is recommended2 for chronic disease alongside castration (medical or surgical).

Beta haemolytic Streptococci have a predictable antimicrobial susceptibility, therefore in accordance with CLSI guidelines3 , susceptibility testing is not routinely performed by IDEXX UK. However, there are increasing reports of resistance of this group of bacteria to fluoroquinolones which would preclude this group of antibiotics from being used. Additionally, there is data to support that the use of fluoroquinolones for treatment of Streptococcus canis may be involved in the increased emergence of canine streptococcal toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis (NF)4 . On top of this, fluoroquinolones should only be used when first-line antibacterials are inappropriate or ineffective.1

The patient was started on TMS 20mg/Kg PO BID. A Schirmer tear test was performed as a baseline and another test scheduled for 10 days and 20 days later given the potential risk of development of dry eye. Haematology and biochemistry were also reassessed after 15 days of treatment in case of potential adverse effects from use of TMS; results were unremarkable and the neutrophilia had resolved.

Follow up

The patient was admitted for surgical castration 7 days after starting antibiotic treatment and the owner reported increased energy and better appetite. Two weeks after castration the prostate was already significantly smaller; 6 weeks after castration the prostate was very small in size. Although we recommended to repeat the prostatic wash (cytology and culture) around 7 days after the end of the treatment to confirm complete resolution, the owner elected against this.

Comments

This case highlights the need to perform a complete minimum database (MDB) at the start of the investigation rather than considering only performing parts of it. In this case, with very vague clinical signs, haematology, and biochemistry with electrolytes were largely normal and urinalysis was crucial in raising the suspicion of urinary/reproductive problems and directing subsequent tests. Prostatitis is more common in middle-aged to older entire dogs. Clinical signs of prostatitis depend on whether the prostatitis is acute or chronic and can range from vague non-specific findings (e.g. anorexia, and depression) to severe systemic signs of illness with sepsis. Patients with chronic prostatitis frequently are asymptomatic or have minimal clinical signs.

In cases with acute prostatitis, on rectal examination, the prostate is frequently enlarged, painful and possibly asymmetrical while, in chronic cases it is common for the prostate to have a normal size (for an entire male) and be symmetrical and non-painful. The absence of ultrasonographic changes does not preclude a diagnosis of prostatitis, especially if chronic.

Entire males that develop a urinary tract infection are considered at high risk of having prostatitis. As such, in entire males, the diagnosis of prostatitis is often made presumptively by identifying a proven urinary tract infection (i.e. patient with appropriate clinical, inflammatory urine sediment and a positive urine culture on a cystocentesis sample). However, in some cases of prostatitis, especially if chronic, the urine culture may be negative and therefore a prostatic wash is recommended to confirm the diagnosis, identify the causal organism and help choose the most appropriate treatment.

Prostatitis can be difficult to clear as the blood-prostate barrier is quite effective in preventing many antibiotics from penetrating the prostatic parenchyma and therefore this should be kept in mind when choosing antibiotics (see above in treatment plan). Castration (surgical or medical) is recommended for all patients with prostatitis and it has been suggested that castration should be delayed until the infection is controlled to avoid sequestration of infectious agents in the involuting prostate, hence why castration was not performed immediately in this patient.

Patient reports

Haematology

Chemistry

Urinalysis

Microbiology

Pathology

References:

- BSAVA/SAMSoc PROTECT ME poster https://www.bsavalibrary.com/docserver/fulltext/10.22233/9781910443644/bsava_samsoc_protectmeposter_011118web. pdf?expires=1553681643&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=7D8967579B108A0A5B5C8471BE80B8AF

- International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases (ISCAID) guidelines for diagnosis and management of bacterial urinary tract infections in dogs and cats. Weese J S et al (2019) The Veterinary Journal, Volume 247, May 2019, pp 8-25.

- CLSI. Performance standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests. 13th ed. CLSI standard M02. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2018

- A fluoroquinolone induces a novel mitogen-encoding bacteriophage in Streptococcus canis. Ingrey KT et all (2003) Infection and Immunity, Volume 71, 6, pp 3028-3033.